|

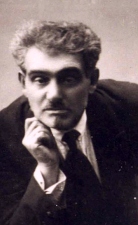

Zalman Kaplan became

a photographer less than 40 years after the introduction of the art in 1839

(by Daguerre in France) and just a few short years after the invention of

the glass negative which allowed both retouching and the printing of

multiple prints on paper.

|

|

|

|

|

Zalman Kaplan |

|

| |

|

Kaplan was a

master of posing and lighting. His camera room had two glass sides and a

glass roof. Most portraits were made by natural light in Europe and the

U.S. until after WWI. Kaplan initially used a large view camera and plates

about 6 x 8 inches. Prints were made on albumen paper, the emulsion

suspended in an eggwhite mixture. Later, he changed to rich, browntoned

carte postale paper from Germany. Contact printing was also the rule. The

retouched negative was sandwiched with a piece of photographic paper the

same size as the negative and exposed to the sun. Compared to other

photographs of the era -- both in Europe and the U.S. -- Kaplan Portraits

are in the superior quality category. His posing was, for its day, more

relaxed than most -- in spite of the one to three second exposures. The

outdoor poses are very casual and ahead of their time. The surviving Kaplan

pictures -- even those almost 100 years old -- are unfaded due to extra

steps taken to fix and brown or goldtone the prints. Faces, even in large

groups, were painstakingly retouched on the negative so each person looked

his or her best. It is easy to see that Kaplan (and his subjects) had a

deep sense of history for each image that was recorded.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Zalman Kaplan

Studio |

|

|

| |

|

In towns

throughout Europe -- and the U.S. -- the photographer's studio was

frequented by all economic groups. Some came to simply record themselves

looking their best or to have a portrait to give to loved ones. Some came

to commemorate an event like a marriage, a visit from an out-of-town

relative, or a family member going away. Or, groups of good friends just

came to be photographed together for fun. Amateur photography was rare so

studios were very busy. Daily visits to see the new pictures in the Kaplan

showcases became a tradition in Szczuczyn. With the military as an early

client, Kaplan often photographed on location both outdoors and inside. He

completed large assignments of photographing area monuments and buildings

for the Czar's army and was presented a gold watch by the commander for the

superior job. Kaplan also sold photographic postcards of his town to

tourists and army personnel. He also documented and sold group photographs

of classes for church, secular, and Jewish schools. His group portraits of

Jewish organizations and committees photographed solely by window light

inside buildings are remarkable even by today's standards.

Of the tens of

thousands of Kaplan photographs made between the 1890's and 1941, three main

groups have survived. First, there are family portraits, school, and club

photographs that remain with Polish families in Szczuczyn. Many of those,

however, were destroyed in World War II -- as were those in the possession

of the city government. The entire Kaplan negative archive was destroyed

during the Holocaust. Next are the photographs taken for Jews leaving

Szczuczyn before World War II for the U.S., Palestine, Canada, Mexico, many

South and Central American countries, Australia, New Zealand, and

elsewhere. Today, with that generation all but gone those pictures are the

only way we can see how they looked and how they lived. Included in this

group are the photographs brought to Canada by the Kaplan sons and those

later mailed to them by their family in Szczuczyn.

A third group

that is now being discovered are the Kaplan photographic postcards mailed by

World War I German soldiers to their families and a few in early Polish

history books. |